Abstract

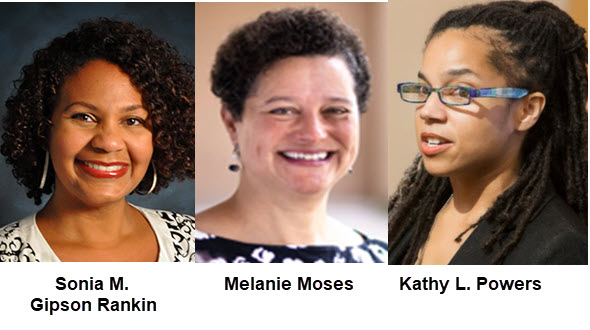

Excerpted From: Sonia M. Gipson Rankin, Melanie Moses and Kathy L. Powers, Automated Stategraft: Electronic Enforcement Technology and the Economic Predation of Black Communities, 2024 Wisconsin Law Review 665 (2024) (208 Footnotes) (Full Document)

In the landscape of post-pandemic economic recovery, U.S. cities have found a way to bridge budget deficits: automated traffic enforcement. The implementation of speed cameras and advanced traffic enforcement technologies marks a significant shift in urban fiscal strategy. However, this solution is casting a shadow over Black communities, which increasingly feel the brunt of this enforcement.

In the landscape of post-pandemic economic recovery, U.S. cities have found a way to bridge budget deficits: automated traffic enforcement. The implementation of speed cameras and advanced traffic enforcement technologies marks a significant shift in urban fiscal strategy. However, this solution is casting a shadow over Black communities, which increasingly feel the brunt of this enforcement.

In the heart of Chicago, young entrepreneur Rodney Perry unwittingly became a symbol of a contentious policy. While launching his new business, Perry experienced an unexpected twist: a barrage of traffic fines. Within a year, Perry was saddled with eleven traffic tickets, a considerable number for marginally exceeding new, stricter speed limits. The financial fallout was severe: over $700 in fines, a Denver boot immobilizing his vehicle, and the added burden of borrowing money to clear his dues.

Perry's story is a microcosm of a larger, troubling pattern. Black communities--already navigating the complexities of post-pandemic recovery-- find themselves disproportionately targeted by these predatory automated enforcement tactics. The use of technology, while ostensibly a neutral tool to generate revenue for cities, is inadvertently exacerbating existing inequalities.

This raises crucial questions about the equity of such policies, highlighting a scenario where measures intended to bolster city finances are placing an undue strain on communities that are the least equipped to bear it. This practice raises critical questions about the fairness and impact of such policies, especially in neighborhoods where every street corner seems to have a watchful camera. While aimed at enhancing road safety, these measures hint at a deeper narrative of disproportionate enforcement and the burden it places on the community's shoulders, challenging the balance between fiscal objectives and the goal of genuinely safer streets.

*668 Traffic enforcement cameras frequently ignite debates over fairness and equality. A central concern is their disproportionate impact on low-income and minority communities, particularly Black and Hispanic communities. The phenomenon of “driving while Black” highlights a troubling pattern: Black drivers are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, threatened, or harassed by police. The financial repercussions from traffic tickets disproportionately burden these drivers, often leading to debt and a higher likelihood of entanglement with the criminal legal system even after a routine traffic stop. Automated traffic enforcement expands the surveillance and punitive experience of driving while Black.

This context is vital when considering the future of automated traffic cameras and facial recognition technology. Contrary to the assumption that algorithms are impartial, these systems can perpetuate racial, gender, and other biases. The uneven distribution of cameras may result in biased enforcement, disproportionately targeting certain communities. Moreover, traffic camera fines pose an additional financial strain on those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, exacerbating existing inequalities. This reality calls for a critical reassessment of the use and implications of automated enforcement systems to ensure they do not perpetuate bias.

This Essay explores how automated traffic enforcement is stategraft, when public officials illegally transfer property to public coffers, and in this case, using electronic means that accelerate the harm, creating *669 atuomated stategraft. Part I describes automated traffic enforcement, its use, technological foundation, and concerns about the disparate impact of this technology. Part II outlines how automated enforcement generates profit and litigation. Part III presents concerns about disparate automated enforcement technologies and recommendations to address safety and equity. The Essay concludes with a call to continue to safeguard the American public from automated stategraft in an age of technology-enabled surveillance.

[. . .]

Automated enforcement can become automated stategraft. While automated traffic enforcement has potential to increase safety, it also *706 raises profound ethical, legal, and social concerns. Far from being passive observers, automated systems impose disproportionate financial and psychological burdens on Black communities, undermining already low trust in law enforcement and exacerbating economic disparities. Increased surveillance coupled with facial recognition technology and other automated responses shifts the burden of proof to those accused of violating traffic laws, and bias in how such systems are trained and deployed will burden some populations more than others. Even when intended to improve safety, these technologies may not address the root causes of traffic safety issues unless they are deployed along with other safety enhancements, many of which cost money rather than increase revenue. Automated traffic enforcement mechanisms are seen as profit generators that worsen the burden on already socioeconomically challenged communities rather than increasing their safety. A critical reevaluation of automated traffic enforcement is essential to address systemic injustices and drive transformative change. Cities and municipalities have an opportunity to increase community trust by deploying effective traffic management that uses technology to effectively balance safety, fairness, and community welfare. To do so, they must prioritize equity, evaluate and mitigate bias, protect privacy, and involve local communities in decisionmaking.

Professor of Law, University of New Mexico School of Law; J.D. 2002, University of Illinois College of Law; B.S. 1998, Morgan State University.

Professor of Computer Science and Special Advisor to the Vice President for Research for Artificial Intelligence, University of New Mexico; External Faculty, Santa Fe Institute; Ph.D. 2005, University of New Mexico; B.S. 1993, Stanford University.

Associate Professor of Political Science and Associate Chair of the Department of Africana Studies, University of New Mexico; External Faculty, Santa Fe Institute; Ph.D. 2001, The Ohio State University; M.A. 1995, State University of New York at Stony Brook; B.A. 1993, Northwestern University.