Abstract

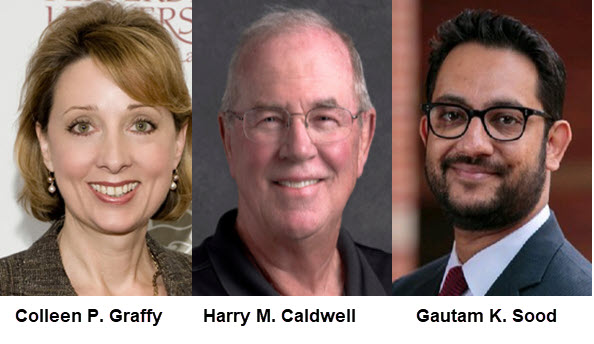

Excerpted From: Colleen P. Graffy, Harry M. Caldwell and Gautam K. Sood, First Twelve in the Box: Implicit Bias Driving the Peremptory Challenge to the Point of Extinction, 102 Oregon Law Review 355 (2024) (249 Footnotes) (Full Document)

The historical arc for the peremptory juror challenge is headed toward its demise. Such a profound assessment will strike many practitioners of jury trials as startling, but for those monitoring recent legislative and judicial developments, the specter of change is looming.

The historical arc for the peremptory juror challenge is headed toward its demise. Such a profound assessment will strike many practitioners of jury trials as startling, but for those monitoring recent legislative and judicial developments, the specter of change is looming.

Peremptory challenges were devised under English common law to aid in achieving an impartial jury and to protect the accused from the excesses of the Crown. Yet, over time, United States prosecution and defense lawyers have manipulated peremptory challenges to achieve not an impartial jury, but a jury partial to their cause. Further, in the United States, prosecutors have manipulated peremptory challenges for a more invidious purpose: to exclude Black individuals from juries.

The Fourteenth Amendment grants citizenship to “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States” and provides all citizens with “equal protection of the laws.” As far back as 1879, in Strauder v. West Virginia, the Supreme Court decreed that laws barring Black citizens from jury service were unconstitutional. After ending upfront discrimination, peremptory challenges became the instrument of choice to discriminate through the back door.

Despite the Strauder decision and federal legislation outlawing race-based discrimination, excluding Black citizens from juries not only continued through peremptory challenges but was endorsed by the Supreme Court's deference to state court decisions. It was not until the infamous “Scottsboro Boys” case in 1935 that the Supreme Court finally called out local and state officials for illegally excluding Black individuals from juries the practice continued through more selective peremptory challenges.

In 1965 the Supreme Court reversed that trend when they held that peremptory challenges could not be used to intentionally exclude Black individuals from jury duty in Swain v. Alabama. However, the Court required proof of intentional discrimination, a very high bar, allowing the system of bias to continue.

The 1986 case Batson v. Kentucky overturned Swain and allowed the defendant to prove racialbias in jury selection by pointing to a pattern of peremptory strikes showing discriminatory intent. Justice Thurgood Marshall, concurring, warned that although the new standard was a step in the right direction, its application left open a loophole allowing prosecutors to discriminate as long as they gave a race-neutral explanation for their strike. Justice Marshall went on to note that proving a prosecutor's motive behind a pretextual discriminatory strike would be difficult, and the only way to truly end racial discrimination would be by “eliminating peremptory challenges entirely.” Chief Justice Warren Burger, dissenting, argued that such an argument was too extreme, maintaining that “[a]n institution like the peremptory challenge that is part of the fabric of our jury system should not be casually cast aside.”

Thirty-two years post Batson proved both Justices right. Study after study showed that prosecutors were continuing to use peremptory challenges to strike Black prospective jurors and that the racially neutral stated reasons were sufficient to obfuscate allegations of discrimination, just as Justice Marshall predicted. And just as Justice Burger asserted, neither states nor the federal government have been able to cast aside the practice of peremptory challenges casually.

It was not until 2018, after mounting criticism focused on the inadequacies of Batson, that Washington became the first state to close the Batson loophole. California followed suit in 2022 along with Colorado, Connecticut, and New Jersey. In 2022, Arizona concluded that further tinkering and tailoring of Batson would not cure the problem and heeded Justice Marshall's solution by becoming the first state to abolish peremptory challenges entirely.

States are now at a crossroads. Since Batson, objections during jury selection and piecemeal judicial modifications to its application have proven ineffective at rooting out racially discriminatory peremptory challenges. States must decide whether to follow Washington's lead and revise the Batson framework, pursue Arizona's approach and eliminate peremptory challenges altogether, or simply maintain the status quo from the 1986 Batson decision.

This Article argues that states should follow Arizona and abolish peremptory challenges entirely. The original justification for creating peremptory challenges--to aid in ensuring an impartial jury to protect the defendant--is not served by their continued use. On the contrary, peremptory challenges are now a tool for advocates to create a partial jury to the detriment of the accused and should be ended.

[. . .]

Returning to the question posed at the outset of this exercise, should states follow Washington's lead and revise the Batson framework as Justice Burger put forth, or should American courts follow the Arizona model as recommended by Justice Marshall and abolish peremptory challenges altogether?

Critics of abolition argue that eliminating peremptory strikes will upset well-established precedent in jury selection procedures, and because they have “been ... part of the common law, statutes, and court rules for over 700 years,” peremptory challenges still ought to have a place in our system. That analysis is unpersuasive given peremptory challenges' historical use, nor does it justify what the empirical and scientific evidence demonstrates--peremptory challenges are a mask for explicit and implicit bias that cuts at the very fabric of our justice system.

Several truths emerge from this Article concerning peremptory challenges, biases, and the various approaches to combat bias in jury selection. The first truth is that the Batson approach is fatally flawed. As demonstrated in contemporary studies, it is ineffective in combating discriminatory peremptory challenges. The gaping hole in Batson is that specious race-neutral reasons could be brought forward to mask discriminatory intent--a testament to its inadequacy. Furthermore, trial judges' willingness to accept an advocate's specious reasons for a challenge, out of fear of impugning the character of the advocates, compromises Batson's approach. Frankly, the extensive litany of Batson's jurisprudence is a barometer for evaluating the inadequacy of its approach.

The second truth is that while the Washington model theoretically plugged the oft-abused “race-neutral” hole of Batson, it is arguably optimistic. After all, the model's reliance on a bench officer to unilaterally determine whether an advocate's peremptory challenges may have been influenced by implicit bias is squarely disconnected from the current state of science and our collective constitutional goal of a consistent and accurate application of the law to all parties at trial.

While it is commendable that states following the Washington model have embraced the role that implicit bias plays in decision-making, it is not reasonable to presume that judges have the wherewithal and clairvoyance to enter the minds of advocates based on an individual decision made about a juror and accurately decipher the advocate's motivation. Implicit biases are unconscious by their nature and virtually invisible to the holder, such that a decision-maker may not even be aware of the reason they made the decision they did. The new Washington framework makes nearly every strike of any prospective juror--irrespective of their background--subject to scrutiny for possibly being discriminatory. This fact alone renders the peremptory challenge an invitation for an allegation of discrimination--whether opposing counsel raises the allegation earnestly or not.

Because the new Washington standard makes all peremptory strikes vulnerable to enhanced scrutiny, what guarantee or trust can we have in a bench officer's ability to decipher biased from unbiased challenges on a consistent basis? Are these bench officers being trained to look for cues to assist in their determinations, or are the determinations arbitrary? Can it be the case that the dismissal of a Black juror on one case was for biased reasons, while another was not? Why? How might such a determination be made? Can advocates appearing within these courts be prepared to predictably know how to respond to such allegations? Will judges be required to produce a criterion that they will apply before trial begins, or will their own snap decisions about whether an advocate's strike was biased be subject to their own implicit biases about the advocate? How will we know it was not?

Unquestionably, the Washington model identifies the right problem but the wrong solution. To appropriately solve this problem, we must either agree to abolish peremptory challenges altogether as Arizona has prescribed, or we must drastically rethink the entire peremptory challenge framework.

The third truth is that the Arizona model eliminating peremptory challenges, while at first blush seemingly radical, is the most prudent approach. If one accepts that identifying implicit bias is a bridge too far, then reducing juror challenges to only for-cause challenges that are more readily surfaced is perhaps the most realistic path forward.

The Arizona model recognizes the difficult reality of identifying implicit bias and therefore relies on the random nature of the venire made up of one's peers. Prospective jurors are randomly selected, subjected to questions designed to identify any cause challenges, and then sworn in and seated. There is no opportunity for advocates to manipulate the composition of the jury with peremptory challenges because there are no peremptory challenges.

The English common law devised peremptory challenges to protect the accused from the excesses of the Crown and create an impartial jury. As the system became fairer to the defendant, and the peremptory challenge safeguard became unfairly used by the defense, Parliament abolished them. Peremptory challenges were no longer needed to ensure an impartial jury and were being used to create a partial one. We have come to a similar crossroad in the United States. Evidence shows the discriminating role of peremptory challenges used to create a partial jury. Whatever value peremptory challenges had in the United States, as with England, they no longer serve their purpose and have a detrimental effect on our justice system. The fix-it approach of Batson is fatally flawed; the Washington model simply creates different challenges. The Arizona model is the best path to follow if our goal is to end discrimination in the jury selection process rather than simply hide it. We urge other states to follow Arizona's elegant solution: if peremptory strikes are being used to discriminate, eliminate peremptory strikes, and put the “first twelve in the box.”

Associate Professor of Law at Pepperdine Caruso School of Law. Barrister and Master of the Bench, the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple.

Professor of Law at Pepperdine Caruso School of Law and Director of Trial Advocacy. Former prosecutor in Santa Barbara and Riverside counties.

Adjunct Professor at Pepperdine Caruso School of Law and Chapman University Fowler School of Law.